I have a poem for you today. No, come back! It’s not mine. I’m going to share this poem, and then I’m going to talk a bit. I hope you stick around.

There Will Come Soft Rains

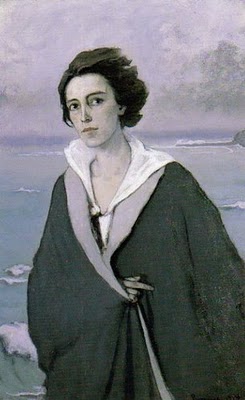

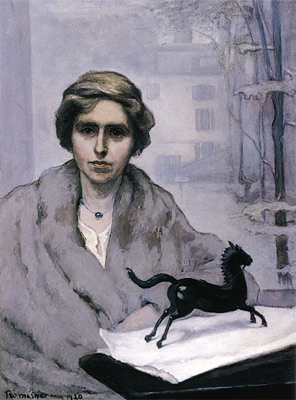

Sara Teasdale, 1884 – 1933

(War Time)

There will come soft rains and the smell of the ground,

And swallows circling with their shimmering sound;

And frogs in the pools singing at night,

And wild plum trees in tremulous white,

Robins will wear their feathery fire

Whistling their whims on a low fence-wire;

And not one will know of the war, not one

Will care at last when it is done.

Not one would mind, neither bird nor tree

If mankind perished utterly;

And Spring herself, when she woke at dawn,

Would scarcely know that we were gone.

***

The reason I wanted to look at this poem is because of Ray Bradbury. After all, it’s why I know the poem. The automated house, the silhouettes, the tree branch, the quiet beautiful disappearing, and the voice still speaking to no one. But look back, and find this poem, and something else beautiful and sad.

I love beautiful and sad.

***

I’m no poetry expert. Obviously. This entire series is about me laying my ignorance and confusion out on the table, confessing that whatever I might have learned in pursuit of my degree fled my head as soon as each paper was turned in. Sorry, undergrad.

In another post I’ll talk about what I remember from studying poetry, and what lacked about it, but for now I’d like to stick with a poem. The Teasdale poem above. It has a lovely quality, which makes me long to live in memories of looking out over quiet Missouri hills in the early morning, or laying in the backyard while Bambiland scampered around me. At the one house, we called my parents’ backyard Bambiland. It was idyllic. A little pond with fishes, beautiful flowers climbing on a trellis, a forsythia that an adult could hide in, a few raised garden beds, trees and bushes large and small… And on maybe a half-acre. You could still hear the traffic, but I mostly remember the sound of the little pond, and birds.

***

When I was reading A Poetry Handbook, I was surprised how many of the very simple concepts felt like revelations to me. Even the ones I already knew. Iambic pentameter! My goodness. Spondees and dactyls, oh my. And so many types of rhyme. I don’t believe any of them were new concepts (except masculine and feminine rhyme) but something about the presentation worked for me.

Here are some things I noticed about this poem.

Rhyme

When I like a poem that rhymes, it’s generally because the rhyme isn’t intrusive, or I like it in spite of the rhyme. With this being in couplets, and so many other aural things going on, I don’t mind the rhymes existing.

Alliteration

Speaking of other aural things going on. This is the thing that gets me most, I guess. Swallows circling with their shimmering sound… Feathery fire…Whistling their whims. These things are important to me.

If I had to guess, at this early stage of my terrible studies, I’d say the thing that matters most to me is the sound of the language. If it’s free verse that just sounds like talking, like sentences, then what’s the point? Honestly, what makes that poetry? I suppose calling it that. But read a poem that confidently takes language and shapes it into something that delights the ear, and even the mouth, and that seems like a little bit of poetic magic to me.

That first phrase I called out… I think it’s the most blatant to me, and sets me up to really notice the others. I just want to roll the words around in my mouth, taste them like a good whiskey. Swallows circling with their shimmering sound. It’s not, I don’t think, it’s not a hiss of a snake sort of sound. It’s the susurrus of birds, the flickering rush of hundreds of starlings, blackbirds, swallows, moving as one in the sky.

Enjambment

Let’s take a breath.

Okay.

In the first three couplets, you get these lovely images of nature, with beautiful word choice that causes it to flow off the tongue — that’s the alliteration, smooth like a spring breeze. Quiet ideas of rain, night sounds, trees gently moving in air.

And then you hit the fourth pair. Though those ‘n’ sounds are soft, they stop you. Not one. Stop. Maybe it’s the ‘t.’ Probably! Especially after the gentle, smooth motion of the third couplet, this one changes the poem. Turns it around. Just in time for the war. Not one appears twice in one line, and then — suddenly — she breaks the phrase. It’s kind of violent, compared to the rest. Though there’s no pause written, the line breaks, snapping the phrase in pieces, like the war and the apathy break the poem right here.

Nature won’t care if we all kill each other.

Spring will still come. Dawn will brighten the landscape. The war will be over but no one will be there to claim victory.

And yet there will come soft rains.

***

I don’t have a specific structure in mind for these posts about poetry. I’m open to ideas. I only have a few basic ideas, but they’re deep wells.

Your turn!

Have you read this poem before?What did you think? I would be utterly delighted if you had comments or questions or thoughts of any kind.